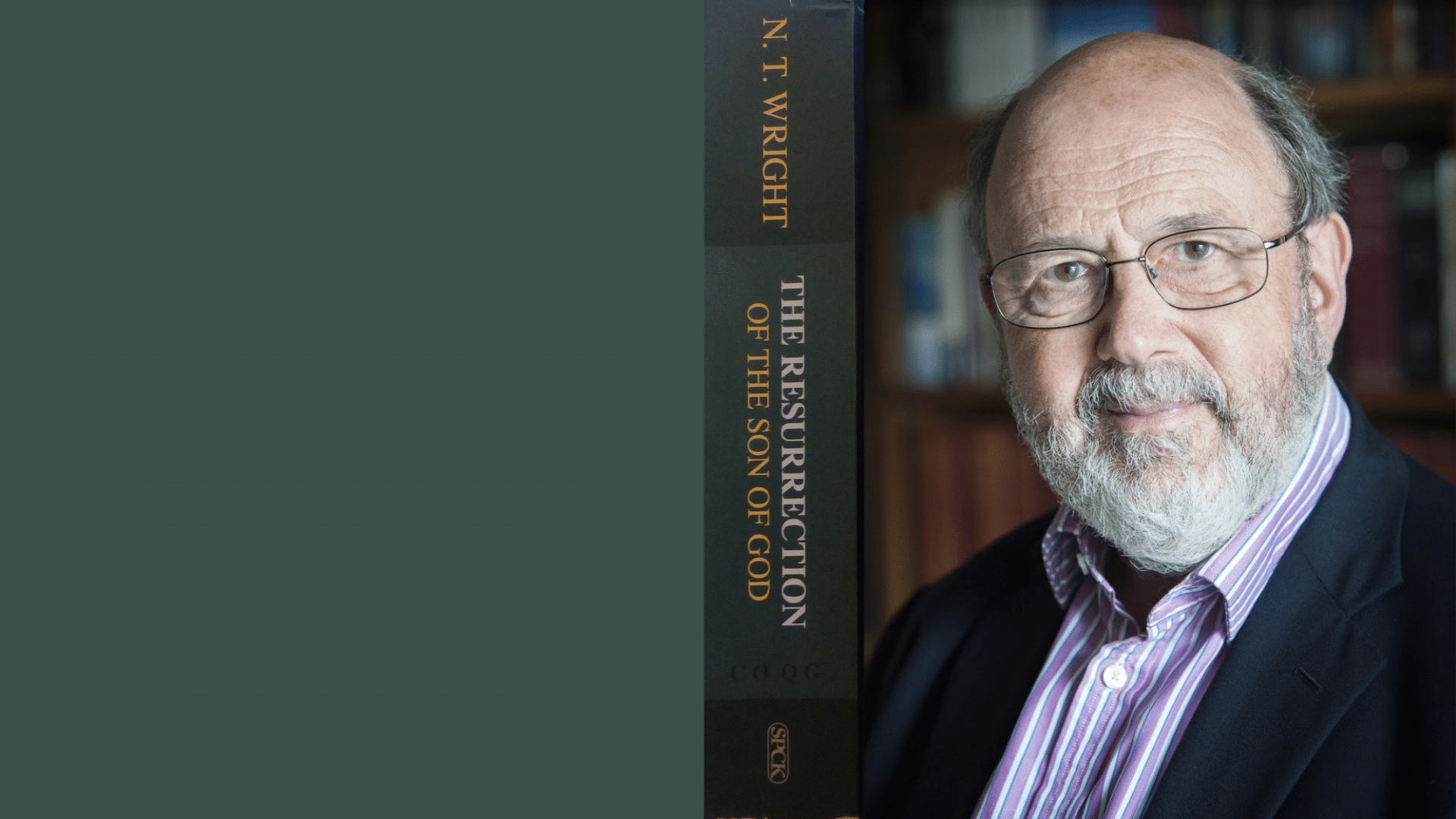

An interview with N T Wright

Why do you think theological writing is important to the church today?

Jesus called us to love God with our minds as well as heart, soul and strength. If the church as a whole isn’t doing that, its thinking – and then its living, preaching and praying – will be shaped, or rather pulled out of shape, by other ways of thinking, and ultimately by sub- or anti-Christian ideologies.

Do you have any writing tips for an early career theologian?

When C S Lewis was asked this, he said, Always be sure exactly what you want to say, and then take care that you say exactly that. In other words, avoid fuzzy or fluffy thinking and writing. One way of doing this is to read great writing of which Lewis is of course a classic example. Get a sense of how his sentences and paragraphs work and then, when you’re starting to write, ask, ‘How might Lewis have said this?’

Can you tell us a bit more about your prize-winning book The Resurrection of the Son of God: Christian Origins and the Question of God (2003). What inspired you to write it?

It was in a sense an accident. It was supposed to be the final section of Jesus and the Victory of God (2006); there wasn’t room in that book, so I put it off. When I was then invited to teach for a term at Harvard Divinity School (late 1999) I decided to do a whole course on the resurrection – only to discover, out there in the supposedly scholarly world, all kinds of fuzzy and silly writing on the subject which needed to be cleaned up. So I had (as it were) to take several steps back and work slowly forwards through the whole world of ancient thought about life after death, and then to locate the early Christians within that . . . it was endlessly fascinating and the payoff was great: the argument for Jesus having been bodily raised from the dead became stronger and stronger. So it was an exciting book to write!

What impact has winning the Michael Ramsey Prize had for you?

I think the main thing was the ongoing sense of astonishment that not only some of the leading theologians who read it but also some of the other famous people on the panel had actually liked it! In a sense it provided a real boost to the morale which sustained me through the subsequent years.

Recently you have had books published on Galatians (Eerdmans, 2021), God and the pandemic (Zondervan & SPCK, 2020) and History and Eschatology (SPCK, 2019).

Could you tell us something about how your theological thinking has developed since you won the Michael Ramsey Prize?

History and Eschatology was the 2018 Gifford Lectures which enabled me to explore the philosophical and theological background to modern NT scholarship in a way I hadn’t done before; a major point there was working out the ways in which ancient Epicureanism came back with a bang and has shaped so much modern western thought – and the way in which many western Christians have responded by reaching for Plato!—as though there wasn’t already a perfectly good biblical metaphysic within which the NT makes the sense it does. In particular, I was able to explore the theme of Temple and Creation which is normally absent from both protestant theology and exegesis but which is massively important.

The Galatians commentary enabled me to revisit many Pauline questions and to emphasize the central importance – over against western individualism which easily collapses into ethnic separation – of the multicultural, multilingual, multiethnic church as the primary evidence to the powers of the world that the creator God is King and that the redeeming Jesus is Lord.

The ‘pandemic’ book enabled me to explore the importance of the biblical tradition of lament in a way I hadn’t done before. There is far too much mechanistic, rationalistic thinking about. We need to put Jesus at the centre of the picture and work out theology from there, rather than setting up a classical picture of a figure we call ‘god’ and then try to cut Jesus down to size to fit.

The Michael Ramsey Prize aims to bridge the gap between popular and academic theology. What areas of theology do you think are under-addressed in popular discourse and why do you think this is?

We need urgently to explore the goodness of creation: to re-read Genesis 1 and 2 and the way they are retrieved (e.g. in Mark 10) by Jesus and in the NT. We have treated questions of behaviour as trivial, whereas the NT sees them as part of the goodness of creation and the launching of new creation. . . but this requires quite a re-think for many people who are still wedded to the platonic going-to-heaven narrative rather than the biblical on-earth-as-in-heaven narrative.

Is there a book (or books!) that you have read recently which you would recommend?

What are some books (of any genre) you regularly reread and why?

G. B. Caird, The Language and Imagery of the Bible is a superb overview of the way biblical language works, written in an engaging style with clear examples. Josephus, The Jewish War – we need to regularly remind ourselves what was really going on in the Middle East in the first century and the way in which thoughtful Judaeans perceived the crisis. C. S. Lewis The Discarded Image and Studies in Words.

Poetry – Hopkins, Eliot, Micheal O’Siadhail. William Golding The Double Tongue. His last book, brilliant, with (to me) a heart-stopping ending.

What books have most profoundly shaped your theology?

- Caird, as above; also his short Jesus and the Jewish Nation.

- C. S. Lewis, Miracles. U. Cassuto, Commentary on Genesis.

- Richard Hays, Echoes of Scripture in the Letters of Paul.

- B. F. Meyer The Aims of Jesus.

- The wealth of books on the second-temple Jewish world which appeared in the 70s and 80s, e.g. the revision by G. Vermes et al of Emil Schuerer’s The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah.

- Commentaries on Romans by Cranfield and Kaesemann (even though I profoundly disagree with both of them).

- Albert Schweitzer’s books on Jesus and Paul (with the same caveat).

- Oliver O’Donovan Resurrection and Moral Order.

- John Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One.

- A. C. Thiselton, The Two Horizons.

Of course the real answer is: Paul’s letters to the Romans and others.

*Please note that the views expressed in these interviews are those of the authors themselves and do not represent the Michael Ramsey Prize or the Archbishop of Canterbury.