An Interview with Luke Bretherton

Why do you think theological writing is important to the church today?

My answer risks sounding pious. But it is the only true and compelling one I can give. And it is the same answer that Simon Peter gave in a moment of exasperation, a moment when many others were abandoning Jesus out of despair at the difficulty of following him and understanding his teaching. At that moment Simon Peter cries “where else can we go?” (John 6:68). To make sense of a world on fire, to discover meaning and a sense of purpose in a time of fracture that is riddled with oppression and overwhelmed by fear for the future, to learn how to inhabit the Gospel as a word that brings life not death, one can only turn to theology. If we are turning elsewhere – to technology, sociology, philosophy, psychology, or some other word – then our words and actions will not be those that bring life. Our words and actions will be a curse not a blessing. That so much of what Christians say and do today is heard and experienced as a curse rather than a blessing is in large part because we have failed to nourish a rich theological imagination.

Do you have any writing tips or advice for an early career theologian?

To repurpose a saying of John Wesley: read as much theology as you can, talk and argue about theology with as many different kinds of people as you can, both ancient and modern, and immerse yourself in worlds where Christ promises to be present as deeply and fully as you can; that is a life with and for the least, the lost and the last (Mathew 25). That way theology will be neither a set of abstract dogmas nor an exercise in writing erudite footnotes on classic texts. It will be a way of life. It will be faith seeking wisdom about how to live here and now. It will be heartfelt prayer. And what you write will matter because it will emerge from the existentially urgent questions posed to you by a life with those you love and care about – both among the living and the dead.

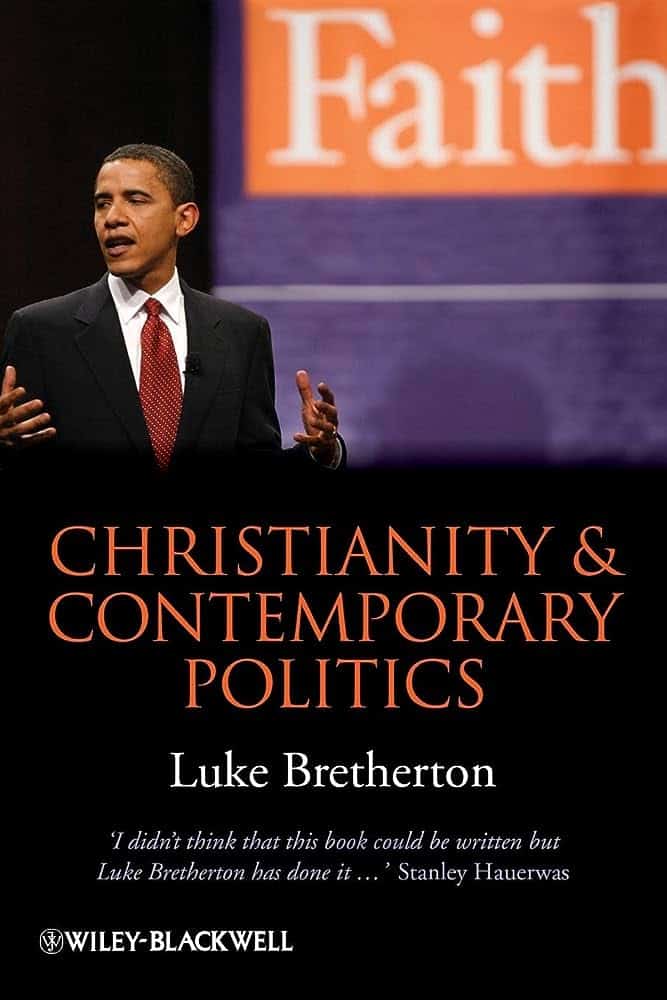

Can you tell us a bit more about your prize-winning book Christianity & Contemporary Politics (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). What inspired you to write it?

The book emerges from a set of questions and problems I kept running into among Christians deeply immersed in the world of politics as well as by those doing mission and ministry in different contexts. These questions also emerged from trying to make sense of my own experiences growing up in London and then working for a number of years in the post-Communist societies of Central and Eastern Europe. In many ways the questions I encountered are one’s I’ve wrestled with in much of my work. And they are variations on the question of what it means to fulfil the command to love thy neighbor.

The first is, what is the appropriate response to the poverty, suffering, and injustice one encounters in trying to love one’s neighbors? The second is: in loving my neighbor, how can I keep faith with my distinctive commitments while also forming a common life with neighbors who have a different vision of life than I do? Another way to put this question is, how should our own roots, our sense of what counts as home, identity, or belonging—that is, what makes us distinctive and particular—be coordinated with and ordered in relationship to those we find strange or who don’t share our beliefs and practices? The third is the question of what kind of power shapes the relationship between myself and my neighbor and how is this power constituted and distributed?

In the book I seek alternatives to common ways in which these questions are answered. Some respond by letting the church be construed by the modern state as either one more interest group seeking a share of public money or just another constituency that can foster social cohesion and make up the deficiencies of the welfare state. The former reduces the church to a client of the state’s patronage and the latter co-opts the church in a new form of establishment, one where the state sets the terms and conditions of, and thence controls the relationship. Another response is for Christians to reconstruct Christianity as a form of identity politics. This entails the church becoming just another minority group demanding recognition for its way of life as equally valid in relation to all others – or the rhetoric of rights – the church decomposing itself into a collective of rights-bearing individuals pursuing freedom of religious expression. A third response is to let Christianity be reconstructed by the market as a product to be consumed or commodity to be bought and sold so that in the religious marketplace Christianity is simply another privatized lifestyle choice, interchangeable with or equivalent to any other. I don’t think these responses are either faithful, hopeful, or loving. So in the book I try to answer these questions through looking at various case studies that provide constructive alternatives to the kind of responses just outlined. These alternatives are community organizing, the sanctuary movement, and fair trade. None are perfect, all are frail and fallen. But through interrogating these cases in dialogue with a wide range of voices, both ancient and modern, the book draws out a theological vision for how to be a faithful witness in the contemporary context.

What impact has winning the Michael Ramsey Prize had for you?

I cannot emphasize enough how winning the prize encouraged and affirmed me in the work I was doing. That senior figures like Sarah Coakley and Rowan Williams, who were judges that year, thought the work was worthwhile and spoke to a wider audience meant the world to me. It gave me confidence to keep going, particularly since my work didn’t really fit with what most people view as theology.

Your book A Primer in Christian Ethics: Christ and the Struggle to Live Well is to be published by Cambridge University Press later this year. Could you tell us something about how your theological thinking has developed since you won the Michael Ramsey Prize?

The year after I won the prize I moved to the United States to teach at Duke Divinity School in North Carolina. I’ve been living and teaching there for the past ten years, years that saw the end of Obama’s presidency and rise of Trump, with all that represents. My colleagues at Duke and my experiences navigating life in a small Southern town very far from the metropolis I grew up in forced me to reckon with things I had not really contemplated in depth before. My colleagues Norman Wirzba and Ellen Davis agitated me to see that theology that did not constantly and consistently think with and through nonhuman life and how God tends and cares for creation is not really theology. Living in London I had done a great deal of work on multiculturalism, and what it meant for Christians to be faithful witnesses in a multifaith and morally diverse society. But my former colleagues Willie Jennings and Jay Kameron Carter taught me to reckon with the ways racism is a theological problem as well as a crisis for modern theology. My colleagues and bible study partners Sarah Jobe, Casey Stanton, and Lauren Winner taught me to read (and preach) Scripture in new ways, in particular, how one cannot really understand the story of salvation without seeing the central role that prisons and the imprisoned play in it. And my doctoral students have taught me so many things, especially how to do the work of theology better. I’ve also come to appreciate in new ways the coinherence of ethics, politics, spirituality, and pastoral care.

The Michael Ramsey Prize aims to bridge the gap between popular and academic theology. What areas of theology do you think are under-addressed in popular discourse and why do you think this is?

There is much written on different political issues but very little on the nature of politics as such. Yet politics rightly understood is the basic form of neighbor love and an understanding of politics is central to faithful discipleship and good church leadership. This lack of theological reflection on the meaning and purpose of politics is strange given that politics is essential to live, let alone live well. We cannot survive, let alone thrive without others. Some kind of common life must be cultivated and sustained if human life is to go on. Politics is the name for generating this common life. The goods we pursue through politics and the quality and character of our political relations determine whether or not we live well. Yet instead of seeing politics as a crucial way in which we work out what it means to love God and neighbor, much popular theology treats politics as either a necessary evil, a failure, or something best avoided.

Is there a book (or books!) that you have read recently which you would recommend?

Eugene Rogers, Blood Theology: Seeing Red in Body- and God-Talk (Cambridge University Press, 2021). This is in many ways a strange and idiosyncratic book but one bursting with life and energy that helps you see and relate to God and the world around you in new ways. Rogers is one of the leading contemporary theologians writing today. Often I don’t agree with him, but he always helps me think harder and better. This particular book throws you. But when you get up, you see the world differently. For the purposes of full disclosure, I should also say that one of the great joys of living in North Carolina this past ten years is becoming friends with Gene who also lives and teaches there.

What are some books (of any genre) you regularly reread and why?

Essays by James Baldwin and poems by Seamus Heaney. How they use language is so richly textured and precise. Their writing has this deeply tender, humane, intimate quality that at the same time opens out new ways of seeing the world, ways that speak to both the wonderous beauty as well as the brutality and banal cruelty of what we do to each other as humans.

*Please note that the views expressed in these interviews are those of the authors themselves and do not represent the Michael Ramsey Prize or the Archbishop of Canterbury.